[➼ updated, 01/03/25: added further information from the excellent Dr. Susanna Braund’s Virgil and his Translators + an entry suggested by Dr. Mike Fontaine. (for the interested: the former has another volume on the way; & the latter, what may be the best possible book for yours truly.)]

[➼ to-do: add Morris, Crane, & Powell; perhaps Hadbawnik, too… though not a big fan of the rather execrable extracts from that translation—“interpretation” might be a better term—that I’ve read.]

I am indebted to FoundInAntiquity for creating a handy reference list (archived copy)—it has been kept open in a pinned tab throughout the project. Thanks, FIA!

I. Usage Notes

II. The Texts

( Dryden | Fitzgerald | Fagles | Mandelbaum | Bartsch | Ruden | Lombardo | Lewis | West | Kline | Fairclough | Humphries | Ferry | Oakley | Ahl | Krisak | Smith | Knight )

III. Conclusion

( Shortlist + Honorable Mentions )

IV. Appendix (“Big Four” & “Best-in-Category” side-by-sides, links)

O. Preramble

I first became (re-)interested in the Aeneid while idly reading through the Wikipedia page on bibliomancy. This was an area of sorcery I had hitherto largely disregarded, because as soon as you hear of it, you instantly know exactly the only form in which it will have been practiced, in the West: that is, with the Bible.1

Imagine my surprise, then, when— actually, hold on; don’t imagine it. I’ll just tell you:

I was surprised! …to find out that, in fact, there is another text with which kings & thaumaturges have practiced the foul art of prediction: The Aeneid (in the “Sortes Vergilianae”).

This blew my mind. This is not the usual sort of text which inspires that sort of imagination; usually, to be the focus of mystical traditions, a work must A.) be vague & confusing, and B.) tell you “hey, this is a text of mysterious power & it’s really great”.

(This sort of thing also appears to work on a personal level, judging by the careers of all the blow-hards & narcissists you know.)

I immediately inferred that Vergil’s Aeneid must be something special, to have so captured the hearts & minds of even wizards. Too, one can hardly be a history buff without encountering mention after mention of the thing. Steve Donaghue, in introducing his review of the Ruden translation, writes:

Virgil took the assignment and went to ground, laboring for ten years (sometimes, if legend is to be believed, at the rate of only a line or two a day). [ . . . ]

But [this biography] . . . certainly doesn’t prepare the newcomer for the staggering scope of Virgil’s subsequent fame. To give you an idea: when Jan Ziolkowski and Michael Putnam put together their 1,200 page study of that subsequent fame, published by Yale in 2008 as The Virgilian Tradition: The First Fifteen Hundred Years, they had to condense. “He has been cited,” wrote 19th century critic F.W.H. Myers, “in different centuries as an authority on the worship of river-nymphs and on the incarnation of Christ.” Augustine was wary of the lure his perfect Latinity posed to the faithful; Savonarola took inspiration from his rolling lines; the writers of the Italian Renaissance worshipped him to a man, and of course he is the object of the most famous literary tribute of them all: he is Dante’s guide and secular patron saint in the Divine Comedy.

One thousand two hundred pages… and the authors could still call it a “preliminary overview”.

And so I decided ol’ Vergil deserved another shot. The question, of course, then becomes: in which translation?!2

There are, apparently, nearly 70 by now, according to FoundInAntiquity’s excellent overview. Luckily, I didn’t know about all 60+ when making my own initial selection—but I am Imperator et Pontifex Maximus of analysis paralysis, and (unlike with some other classics) there appears to be little agreement regarding Aeneid translations.

But do not fear, for the Epoch of Darkness is no longer! Behold, an unusably extensive guide to English translations of the Aeneid!

I. Exordium

This list focuses on 1.) newer translations and 2.) notable older translations, on the assumption that category (1) will incorporate the latest scholarship and category (2) is most likely to be generally of high quality.

If I’ve missed one, please let me know; if I’ve missed any significant features of those I do list, please let me know that also.

One thing I have not considered is the excursical3 information within a given text. Attempting to factor this in adds immensely to the task: three different printings of the same translation might have three different levels of footnoting, three different introductions, appendices ranging from “more lines than the Aeneid itself” to “none at all”, etc.

Order is in, roughly, from best-known to least-known; in the case of a tie, the older translation will be listed first. It is not to be interpreted as best-to-worst!

N.B.:

When I say “includes opening lines”, it’s just a reference to an introductory four lines that (according to Fairclough) “some first-century editor” put in Vergil’s mouth (er, pen)—so this is not, technically, important enough to have under “Notable Notes:”… but I couldn’t think of anywhere better for this detail. And anyway, I like ‘em.

I’m using the term “blank verse”, below, to indicate iambic pentameter; but I’ve not, heretofore, been super well-informed regarding poetics… so if you are able to tell anything about the meter of the translations, where I have not noted it—or know of anything else about a translation I’ve not mentioned—your feedback is requested!

II. The Translations in Excerpt

▼ John Dryden (1697) ▼

Notable Notes: “Heroic (rhyming) couplets”; freely available online (archive); also, it’s the Dryden translation (#1 of the Big Four). C’mon.

We cannot call ourselves acquainted with English poetry in his age and in the next unless we have read his translation, and it is still fascinating to see his mind at play over his great original.

—Robert Fitzgerald

This is it, #1 of the “Big Four” (see footnote #8): the best-known & most-loved, even to this very day—no small feat, for an English work composed so long ago. When Fitzgerald writes that “[i]f anyone then living could have done a great Aeneid, Dryden could,” it seems no more than just.

Fitzgerald’s words certainly appear to be high praise indeed… but here is a prime example of something strange: these very words are from a monograph that is—sometimes sharply—critical of Dryden!4

Fitzgerald is too sophisticated for my barbarous brain to pin down exactly what he doesn’t like about it,5 but it’s clear there’s something amiss:

It fell to John Dryden . . . to produce the English Aeneid, and at the time he did so neither he nor any other Englishmen could manage, except momentarily, the kind of poetry required. They were too interested in improving on it. I do not say this entirely in malice, but with sympathy for the criterion of "sense" and with respect for the cultivated and sometimes noble energy of Dryden's writing.

[ . . . ]

Likewise in poetry, discussion and wit now flourished at a certain remove from discovery and experience . . . Dryden's predicament, then, was not that of being enslaved to the rhymed couplet; it was the enslavement of the couplet itself to a certain style. The example of the French Alexandrine had had much to do with tidying and balancing the English couplet, though Dryden himself remarked on . . . the lightness that made the French language fall easily into logical symmetries. He realized that the genius of his own language might be cramped by these, but they charmed him and his contemporaries . . . Dryden in practice wanted the discursive merits [of prose], a little negligence included, in verse as well.

Ah. Well—of course, that explains it: it was those cursèd French Alexandrines again, exerting their pernicious influence on our boy John, tempting him into French perversions such as wanting discursive merits.6 Just as I suspected—my diagnosis exactly, in fact!

[cough]

Fitzgerald gets a bit less opaque as the essay continues, though:

It is plain from Dryden's own remarks that he felt the inadequacy of his verse and his diction . . . he did not consistently enter into the mind of the original artist to the point of seeing, hearing and feeling the scenes that Virgil created. Most often he wished rather to make a literary artefact answering to another literary artefact, and this satisfied the taste of his contemporaries.

This is not the harshest criticism—both in the sense that harsher words come later in the same piece, and that in general neither Fitzgerald nor the modal classics scholar have truly negative things to say about J. D.—but it is a far cry from the sentiment that we opened with.

Thus does scholarly opinion on Dryden’s Aeneid seem… ambivalent—in an odd way, one that’s hard to square with itself. On one hand, nearly all classicists dismiss the translation as archaic, both in its English & in working from a deficient critical edition;7 as being entirely too free with the Latin (“more of an interpretation than a translation”), and making no attempt to emulate Vergilian qualities in the English; and—for the unsophisticated choice of rhyming couplets (“entirely inappropriate for translation of Latin epic poetry”)—as somewhat wrong-headed ab initio.

…and yet, on t’other (hand), it is near-unanimously fêted as a “must-read”, “sublime”, “evocative and rich” in a way “no other version has yet managed to surpass, or yet even equal”. Too, it is perhaps worth noting that, e.g., in FoundInAntiquity’s list of translations, more respondents remembered Dryden’s translation than any other—nearly twice as many as could recall the next two most well-known (Fagles & Fitzie himself)!

What, then, ought we think?

Fitzgerald references Dryden’s “peculiar excellence” as “[lying] in a whiplike power of statement, swift and flexible but weighted”; and, for my own uncultured part, lines such as:

Through such a train of woes if I should run, The day would sooner than the tale be done . . .

or:

The champion's chariot next is seen to roll, Besmeared with hostile blood, and honorably foul . . .

…might pay for many sins indeed.

If Fitzgerald has caused me to snort at poor J.D.’s “herds of wolves”, and at his Trojans happily ignoring “the groans of Greeks” emanating from the Horse’s wooden belly as they blithely wheel it into Troy, he has also highlighted wherein the work truly is sublime—as well as that Dryden’s ultimate “philosophy of translation” still has a lot to recommend it: (here quoting Fitzgerald quoting Dryden)

I have endeavored to make Virgil speak such English as he would himself have spoken, if he had been born in England, and in this present age . . .

Sounds good to me.

To close—since I have already stolen so much from been so inspired by his monograph on Dryden’s Aeneid—I’ll let Robert S. Fitzgerald make the final judgment:

I hope I have made clear how Dryden's Aeneid suffered from being the rush job that it was, and yet how brilliantly he brought it off. No one else, with no matter how much leisure, has yet achieved a version as variously interesting and as true to the best style of a later age as his was to his own. He allowed himself a complacent sentence or two about it, but the final judgment expressed in his Dedication was severe:

"I have done great wrong to Virgil in the whole translation: want of time, the inferiority of our language, the inconvenience of rhyme, and all the other excuses I have made, may alleviate my fault, but cannot justify the boldness of my undertaking. What avails it me to acknowledge freely that I have been unable to do him right in any line?"

Too severe.

▼ Robert Fitzgerald (1981) ▼

Notable Notes: Blank verse; one of the most popular translations (#2 of the Big Four). Greater fidelity-to-the-Latin than Fagles, less than Mandelbaum / “balanced” (between literal & poetic).

Fitzgerald’s translation is, undoubtedly, a strong contender for “best overall”—at least, as measured by renown; it sits up there with Dryden, Mandelbaum, & Fagles in the “far-&-away most famous” category. Judging by the erudition he displays in the above-plagiarized above–cited article, he well-deserves his spot.

Unfortunately, my copy has no information as to Fitzgerald’s thoughts on his own translation; if anyone knows of such, I’d like to include it.

But then, I suppose I’ve quoted R. S. Fitzergerald, Esq., quite enough already! Suffice it to say, perhaps, that along with being #2 of the Big Four, his work is the one that another of his Big Four fellows (BFFs)8—Fagles—names as his favorite modern verse translation of the Aeneid (& ultimately second only to Dryden, which agrees neatly with my “renown-rank”).

▼ Robert Fagles (2006) ▼

Notable Notes: Blank verse; one of the most popular translations (#3 or #4 of the Big Four). More “literary” / “poetic” than Fitzgerald or Mandelbaum, but less faithful to the Latin.

Fagles writes that he attempted to find a middle ground between A.), a more literal translation, that has “the features of an ancient author”; and B.), a more “literary” translation, that caters to the “expectations of the contemporary reader”—suggesting, later on in his Translator’s Note, that he’s probably erred more to the side of (B). He puts a particular emphasis on “dramatics”, suggesting that the poem was meant to be read aloud & that he attempted to create a translation that is amenable to this.

Fagles also echoes many of the other translators here in suggesting that “plain and direct” & “fast-moving” are important Vergilian attributes, and he provides (as is, apparently, the custom) some confusing-but-cool musings on incomprehensible9 topics such as “the historical Now”:

Similarly, the reader is surrounded by a luminous, recurrent Now that not only captures his or her attention but also makes the reader a witness and even, within one’s private study, a participant in a series of events. It is as if—Gransden again, to whom many of these remarks are much indebted—the “when” of an action is less important than the fact and “how” of its occurrence. And as Andreola Rossi pursues the point, most occurrences in the poem are presented “here and now” instead of “then and there,” as Virgil creates “a forged continuum, even an identity, between the past retold and the present perceived” (p. 130).

[ . . . ]

So frequent is Virgil’s use of the historical present that he can intersperse the imperfect among his verbs, producing a confident shuttling back and forth in time, even within the same verse paragraph. The translation suggests the effect in a more cautious, discretionary way, to spare the English reader some confusion. . . .

Other features of his performance do the same, each reinforcing the energeia of his epic, and each has a bearing, however distant, on the translation at hand. One is Virgil’s reputation . . . for directness of speech, his preference for the plain instead of the “poetic” word, a preference I have often tried to follow.

I find the entire Translator’s Note here to be well-worth reading, and wish to quote the entirety; however, I’ll content myself with the most directly-relevant bit of the pages remaining within (for Fagles’ Note is one of the longest & most extensive of ‘em all):

And perhaps the most epic feature of all is one already mentioned: the pulsing sweep of the narrative itself, borne along by Virgil’s voice, its rise and fall throughout the Aeneid’s length and breadth, “the enormous onward pressure” that C. S. Lewis felt as strongly in Virgil as he did in Milton, “of the great stream on which you are embarked” (p. 45). No wonder Tennyson praises Virgil not only for his ennoblements, for wielding “the stateliest measure / ever moulded by the lips of man,” but also for his sheer kinetic power, his “ocean-roll of rhythm” (“To Virgil”).

[ . . . ]

However remotely, I have sought a compromise between Virgil’s spacious hexameter, his “ocean-roll of rhythm,” and a tighter line more native to English verse. Yet I have opted for a freer give-and-take, for more variety than uniformity with Virgil than with Homer. This may be unavoidable in trying to “unpack” Virgil’s more compressed effects, his virtuoso displays of highly inflected, and deeply suggestive, word order, which can take one’s breath away. In any event, working from a five- or six-beat line while leaning more to six, I expand at times to seven, to convey the reach of an “Homeric” simile in the Aeneid, or the vehemence of a storm at sea or a battle waged on land. Or I contract at times to three or four beats, not when Virgil does (perhaps implying with his half lines that revision is on its way), but to give a speech or action sharper stress in English. . . . All told, I hope not only to give my own language a slight stretching now and then, but also to lend Virgil the sort of range in rhythm, pace and tone that may make a version of the Aeneid . . . engaging to a modern reader.

▼ Allen Mandelbaum (1971) ▼

Notable Notes: Blank verse; one of the most popular translations (#4 or #3 of the Big Four). Probably the most faithful of the B-Four.

Mandelbaum, like many of these literary luminaries, writes some stuff about Vergil that I like the sound of but don’t, quite, truly understand:

Virgil . . . [had] a style that was not only "stately" but, as Macrobius noted in the Saturnalia, was "now brief, now full, now dry, now rich . . . now easy, now impetuous." Also, beginning with a tercet that marked clause or sentence somewhat mechanistically, Dante was to learn from Virgil a freer relation of line and syntax, a richer play of enjambment, rejet, and contre-rejet. The instances belong elsewhere; the lesson of freedom and definition is what is important here. That freedom also reached an area that Dante, the fastest of poets, never fully realized: the rapid shifts of tense in Virgil, the sudden intrusions of past on present and present on past within the narrative sequence itself . . .

He doesn’t appear to offer much insight into his own “principles-of-translation”, though—just a brief mention, in between wringing his hands over the Vietnam war, of wishing to retain the variety in pace, and in word-choice & sound, of the original; and of hoping to avoid the “inert” line-endings that he feels plagued other translations.

Worth noting, perhaps, that Bartsch names Mandelbaum as “close[r] to the Latin” than others (though she doesn’t like his wordiness as much); Steve Donoghue (archive) also offers an endorsement of this version (though he may ultimately favor Ruden; see below):

[Mandelbaum] was the first modern translator I’d ever encountered who esteemed Dryden instead of reflexively sneering at him (the entire body of his poetic work is still mostly only the object of reflexive sneering, which would have baffled the finest minds of his own day, and which baffles my own less-fine mind today). But I’ve also always loved how alive he is to Virgil’s enormous brain at work throughout the poem:

"I have tried to impress what Macrobius heard and Dante learned on this translation, to embody both the grave tread and the speed and angularity Virgil can summon, the asymmetrical thrust of a mind on the move. I have tried to annul what too many readers of Virgil in modern translation have taken to be his: the flat and unvarious, and the loss of shape and energy where the end of the line is inert –neither reinforced nor resisted – and the mass of sound becomes amorphous and anonymous. In the course of that attempt, a part of the self says with Dryden . . . : “For my part, I am lost in the admiration of it: I contemn the world when I think of it, and my self when I translate it” . . .

And I love the end result, the lilting English verse Mandelbaum labors to make out of Virgil’s Latin . . .

. . . “The sky was everywhere and everywhere the sea” is a line Virgil himself would have approved, I think, and Mandelbaum is equally good at evoking the oppressive moods Virgil could do so well: his opening scenes in burning Troy – marauding soldiers racing through the flame-dancing shadows, Aeneas himself running from flashpoint to flashpoint, sword drawn, desperate to save what he can see with his own eyes is past saving.

▼ Shadi Bartsch (2020) ▼

Notable Notes: Verse (iambic hexameter); 1:1 line count; very extensive effort to transpose all elements of Vergil’s Latin into English.

Bartsch clearly knows her stuff when it comes to poetics—see footnote #12—and has clearly put a lot of thought into nearly every aspect of her task. For example, alliteration—although by no means as unusual to retain as hexameter—is not commonly given much consideration, it seems; yet check out this note from Bartsch:

Another well-known example [of Vergilian alliteration] comes as the twin snakes approach the Trojan coast to murder Laocoön and his two sons. The Latin there is full of sibilants, creating an onomatopoeic effect to evoke the serpents’ hiss, and my English, I hope, is pretty hissy too (2.209–11).

The sea foamed and splashed: then they were ashore. Their eyes were flaming, shot with blood and fire. As they hissed, they licked their jaws with flicking tongues[ . . . ]

(This alliteration, however, is not always correlated to the places where Vergil uses it, as my primary aim has been to maintain clarity and meter.)

[ . . . ]

Vergil also uses elision (the disappearance of the final syllable of a word before the initial vowel of another word) to create effects that unfortunately can’t be replicated in English, like his famous description of the “misshapen mass” of the Cyclops (3.658): “monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens.” In Latin this line would lose many of its syllables and run together in a misshapen mass itself: “monstrorrendinforimngens.” My translation simply reads “a gross misshapen massive monster,” using alliteration and a series of run-on adjectives as a substitute for Vergil’s brilliant line. There is only so much one can do!

Even better, Bartsch has some good ideas on the task of a translator: in her Translator’s Note, she writes that she agrees with classicist D. E. Hill that “a translation ‘freed from the text and soaring into literary beauties’ does us no good—if we want to read Vergil.”

Hence, Bartsch wanted not only (archive) to keep the line count the same, but—having a firm idea that Vergil’s verse is “very fast-moving, dense, exciting”—also attempted to keep the lines to a trim six feet (iambs), as in the Latin. Together, these are supposed to give the English-only reader “a radically different experience” from other translations (i.e., as close as possible to reading Vergil’s original Latin). Great!

Alas, as a Modern Academic, she is required by divine law to spend a good chunk of her commentary on all the Marginalized Perspectives & Silenced Voices™ in Vergil… which sort of makes me wonder how faithful a translator one can really be, if the translatee is—evidently—so odious to you.

Still, this is one of only four translations—ever, as far as I’m aware—to have attempted hexameter (the others: Ahl, Krisak, & an 1888 effort by Oliver Crane); and if hers is not literally the sole translation to do the following, as she writes, it is still one of a very, very select company:

. . . I have tried instead [of creating a “work of poetry in its own right”] to create a parallel to the experience of reading Vergil in Latin. To that end, and to the best of my knowledge, this is the only translation that combines all the following features in a single version of the poem: the use of meter, line-to-line correspondence, verses that do not exceed Vergil’s six beats, simplicity of language, a full glossary, fidelity to the original, the Vergilian effects of alliteration and assonance, notes on the text when modern readers might not be aware of the subtext, and of course an introduction.

▼ Sarah Ruden (2021) ▼

Notable Notes: Blank verse; 1:1 line count; extensive effort to transpose all elements of Vergil’s Latin into English. The 2021 printing is the Revised & Expanded edition; original in 2008.

Ruden is—they say—notable for often choosing Anglo-Saxon terms over Latinate ones, which are the more obvious choice (or, perhaps, temptation10). The author of the Introduction to the R&E ed.—Susanna Braund, something of an authority on Vergil translations herself—says that this, along with the effort to keep the lines in 1:1 correspondence, creates a crackin’ good pace; a translation of greater brevity than others, closer to Vergil’s original wordcount than most… yet with “virtually nothing of the Latin” missing, even so. (Braund notes these felicities have been purchased at the price of some line “re-ordering”; presumably, that’s intra-sentence only.)

Steve Donaghue says (archive) much the same, and additionally calls Ruden’s work “the single best Aeneid of modern times” as well as:

. . . the only English translation of the work that a) doesn’t feel like a translation and b) may finally replace Dryden as the yardstick by which all Virgils are measured.

Returning to Braund: she acclaims Ruden’s choice of iambic pentameter:—

The meter itself has a long pedigree in English poetry, starting with Geoffrey Chaucer. In the sixteenth century Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare developed the unrhymed form of iambic pentameter that we call blank verse; in epic poetry this reached its apex with Milton in the seventeenth century, in Paradise Lost . . . while . . . William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Robert Browning [also] embraced blank verse for many of their poetic compositions. The substantial corpus of English poetry written in blank verse has thus accustomed our ears to its typical sounds and rhythms. This makes it an excellent choice [of meter]: just as Vergil’s educated contemporaries were deeply familiar with epic poetry in [dactylic hexameter], so anyone who has delved into English poetry will have read a lot of blank verse. It is the “right” meter for epic.

—and offers some further commentary on Ruden’s style, including a few phrases which are extremely promising (emphasis added to point these out):

Vergil attains and maintains a tone of dignity and gravity in his Aeneid, sometimes leaning toward solemnity, sometimes toward majesty, with only a few playful or comic moments, as . . . in book 5. There is no place for banal or casual language in a translation of the Aeneid. Yet this is a fault afflicting many of the competing translations produced in the past few decades. By contrast, Ruden’s language is free [of this]. Her diction is pitched at a higher level than ordinary speech . . . she has stripped her translation down to the central ideas in the Latin[, giving] it a consistent elegance which carries dignity and gravity. . . . The largely iambic rhythm of the translation guarantees the onward impetus of Latin dactylic hexameters, which can move with rapidity in battle scenes and with sad solemnity in moments of pathos. . . . Ruden demonstrates the kind of self-effacement that is ideal in a translator: she seeks not to impose herself on Vergil but to allow his words and ideas to emerge untrammeled.

[ . . . ]

She observes Vergil’s plentiful use of enjambment: Vergil . . . frequently runs his sentences partway into the next line and introduces a strong punctuation break there. The temptation in English is to end-stop the lines. Ruden usually resists this. But sometimes she breaks Vergil’s longer sentences down into shorter units for clarity. At all times she aims to reflect the elegant fluidity of the Latin.

On the same site referenced above, an interesting interview (archive) with Ruden is available, as well; of particular interest is when Stevie-boy tries to get her to huff some First Female Translator farts with him, and she flat-out rejects it. Hey, I’m liking this translation more & more!

However, I shall contain myself & only excerpt a more relevant bit, I guess:

OL: What other sympathies did you discover in Vergil, in the course of rendering his book into English? What were your major revelations, confirmations, surprises?

SR: I found that there are ways he harmonizes with English. We think of Latin and Italian as smooth. Maybe Italian is, and maybe ordinary Latin is, but Vergil’s Latin is crunchy, particularly in the enjambments and the conflict of accent and ictus (which means that the meter and the accented syllables don’t match). But what keeps you awake at night is that he’s a real, honest-to-goodness genius. He’s not always good, and in commenting on this unfinished poem, scholars sometimes can’t restrain themselves from voicing the scholarly version of “This line is dippy.” But Vergil couldn’t have written an uninteresting, trite line if you’d tortured him to death. In a cerebral way, that’s how he appears to have died, in agony at the mere possibility that he could just write something in the blank spaces, finish up and forget about it, like other authors.

It’s always good to see that sort of appreciation for their subject, in a translator.

▼ Stanley Lombardo (2005) ▼

Notable Notes: Blank verse. Includes opening lines.

Another well-loved translation (although some of that renown might be mere reflected glory from the same fellow’s Iliad). Lombardo, unlike many of the other translators herein, includes the opening four lines about Vergil having previously been a farmer and whatnot; I like that, even if the lines are later additions—to me, they read excellently enough to have been original to Vergil.

Also unlike many, Lombardo doesn’t write about Vergil’s language being “fast-moving”, but rather almost the opposite:

For all of the action and drama in the Aeneid, there is at its core a profound stillness, and a subdued light. If, as the ancient critic Longinus says, the light in Homer’s Iliad is the intense light of noon, and in the Odyssey the magical glow of the setting sun, it is in the Aeneid a chiaroscuro, a play of light amid the shadows of evening, a darkness visible. . . . A twilight mood gathers around almost every scene in the poem. Like Homer, Virgil reflects a complex world steadily and as a whole, but, much more so than Homer, he is consciously reflective as well, both in his melancholy voice as narrator and in the conflicted voices of his characters.

Like Fagles, he wanted his version to be amenable to a dramatic reading (aloud):

The rhythmic line that I have developed in response to the classical hexameter—a line that I have used for Homer and use for Virgil—is based, like much of modern English and American poetry, on natural speech cadences. This is in keeping with the performative qualities of the Aeneid, which although it is literary rather than oral epic was nonetheless intended to be recited, practically sung. Virgil’s word music is more than mortal. . . . I have continued the practices, which I began with the Iliad, of composing for performance as much as for the printed page and of using actual performances to shape the translation process.

“Virgil’s word music is more than mortal”—I like that; really gets you in the mood to read some Virgil!

▼ Cecil Day Lewis (1952) ▼

Notable Notes: (Pseudo?-) verse;* 1:1 line count (I think).

*(See: fotenoot 11.)

Unfortunately, Lewis—though he wrote a fairly interesting introduction re Vergil as a poet, and his aims & considerations when composing the Aeneid—did not write about his own aims & considerations in translating it.

(Note from latter-day KV: Most of the longer entries herein were written near completion of the project, and were I doing it over again, I’d cry. …No! I mean, I’d probably try to quote some of Lewis’ more apposite observations here, so the entry isn’t tooo anemic by comparison with the rest… but at this point, I just want to hit the dam’ “Publish” button.)

▼ David West (1990) ▼

Notable Notes: Prose; among the best-loved of prose Aeneids. More literal / less “poetic” than Ferry’s.

West makes the argument—and, I’m afraid, I tend to agree—that prose “moves us toward pity, terror, or laughter . . . more than the voices of contemporary poets.”

It is true, I think, that prose has had much greater impact in & on our society than has poetry; this is possibly because, as with other arts, our modern versions are up their own asses (if you’ll pardon the French), having abandoned antiquated notions of “rhyme” or “representation” or “beauty”, and other such follies that the uneducated mind perceives as pleasing.

That said, as the original Aeneid was verse, the temptation is great to demand a verse translation. This has certainly been the prevailing approach to the task, and (as evident by this entry’s position on the list) poetic translations seem to have been more successful, on the whole.

Still, to get to grips with the actual story that Vergil tells, one could definitely do worse than choose a prose version.

▼ A.S. Kline (2002) ▼

Notable Notes: Pseudo-verse;11 1:1 line count; freely available online.

Again, I’ve found no record of Kline’s thoughts on translating Vergil; handy to have a free online version that seems well-liked, though. I have seen one person observe that Kline’s version is more accurate to the original Latin than is the modal translation—though I cannot vouch for the accuracy of the observation (as my own Latin still lurks somewhere south of “abysmal”).

▼ H. Rushton Fairclough (1935) ▼

Notable Notes: Prose; parallel text; in two volumes; originally published in 1916, revised twice (1934, presumably by Fairclough himself, and 1999, by one G. P. Goold); well-known as the Loeb Classical Library translation. Includes opening lines.

In electing to write ‘heroic prose’ Fairclough chose the best option. A strictly literal translation . . . is bound, however faithful to the meaning, to lead to unidiomatic language, alien from the original and incapable of reproducing its intended influences upon a receptive mind. Verse renditions must necessarily deviate fundamentally from the original and reflect the talent and principles rather of the translator than of the original poet.

[ . . . ]

Then again noble and magnificent language not only merits but demands some attempt to recapture that splendour in translation. Classic works which have been translated hundreds of times are likely to have led to felicitous renderings of numerous phrases and sentences which it would be a pity to discard for something inferior . . . Similarly Fairclough did not scruple to take over many apposite renditions from previous translators, and in this I have followed him . . .

English which seems excessively old-fashioned will not do, for all that Virgil himself often employs such archaisms. . . . I have retained much of Fairclough’s poetical or elevated English, but banished . . . thou mayest . . . and many such forms, hoping that my replacements will not diminish the elegance of his original.

—G.P. Goold▼ Rolfe Humphries (1951) ▼

Notable Notes: “Loose” blank verse; freely available online (archive).

Humphries writes that this is “a quick and unscrupulous job”, and that he has “taken all kinds of liberties, such as no pure scholar could possibly approve”; but also that he has “been not entirely without principles” and: “tried to be faithful to . . . the meaning of the poem as I understand it, to make it sound to you . . . the way it feels to me.”

I quite like the general “voice” of Humphries in his introduction, and it’s an interesting, if quick, read; the line he has taken in introducing his principles-of-translation is not one that tends to find much favor with me, but he almost convinces me to give it a chance anyhow:

The poem moves, in more senses than one: the thing to do is to feel it and listen to it. Hear how the themes vary and recur; how the tone lightens and darkens, the volume swells or dies, the tempo rushes or lingers. Take in the poem with the mind, to be sure; take it in with the eye as well; but above all, hearken to it with the ear.

[ . . . ]

Working on it, I have been impressed . . . by its richness and variety: to mention only one point, the famous Virgilian melancholy, the tone of Sunt lacrimae rerum, is . . . a recurring, not a sustained, theme. There is much more rugged and rough, harsh and bitter, music in Virgil than you might suspect if you have only read about him. Mark Van Doren . . . [points out that] there is a kind of scholastic snobbishness . . . in the insistence that no man knows anything who has not read the classics in the original. It is better, no doubt, to read Virgil in his own Latin, but still—I hope some people may have some pleasure of him, some idea of how good he was, through this English arrangement.

▼ David Ferry (2011) ▼

Notable Notes: Blank verse; extensive effort to retain feel of Vergil’s Latin in English-suitable verse. More “poetic” / less literal than West’s.

I can do no better than to quote from his introductory note, “On Meter”; the fellow certainly sounds well-versed (heh heh) in the use of language vis-à-vis poetry:

I have not sought to use a dactylic hexameter instrument. In my view, the forward- propulsive character of English speech favors iambic pentameter, in which iambic events naturally dominate, with anapestic events as naturally occurring. Iambic pentameter has relatively few trochaic events; dactylic events, almost never.

Iambic pentameter arises most naturally from the characteristics of English grammar and syntax, and so I am using it here. Virgil’s dactylic hexameter and iambic pentameter have in common that they have (not by accident) histories of being instruments of heroic writing . . . [T]he amplitude and continuous regularity of the line is suitable to the grandeur of the sovereign rhythm of the whole.

[ . . . ]

William Wordsworth said that there’s always something like a pause after each line in unrhymed verse, marking the fact that a new metrical event is conceding, and another new metrical event is beginning to happen. Readers should hear it this way. Maybe not exactly a pause, but an alerted active awareness that this is happening. As Samuel Johnson says, “All the syllables of each line co-operate together . . . every verse unmingled with another as a distinct system of sounds.”

[here he gives two examples]

. . . Two iambic pentameter lines tell, in their continuances, the same story, the rising of the smoke, but each of them with a distinctive individuated truth-telling music.

There is much more that’s worth the reading in the essay; and this is the sort of thing that goes a good way toward convincing me of a translation’s merits—even if my barbarian ear cannot detect such subtleties as, uh, “anapestic events”.

In a final statement, Ferry summarizes “the effort” as:

… to achieve a representation, in the lines as they move forward, line by line, telling the tale, some kind of kinship not only to the sense of the Latin but also to the expressive complexities of implicated discernment and emotion in the lines.

Let’s see, in the lines, how well he’s lined his lines, then:

▼ Michael Oakley (1957) ▼

Notable Notes: Verse (“a line of five stresses separated by one or two unaccented syllables”); extensive effort to mix feel of Vergil’s Latin with clarity-in-reading.

The above description is that given in FoundInAntiquity’s reference-table; since this is not given for any other version, I presume it is unique to Oakley’s—which is, if I’m honest, the entire reason I have selected this translation for comparison. It doesn’t seem to be very well-known, and neither is it recent… but a one-of-a-kind effort deserves at least a look, right?

Well, to judge by the “Translator’s Note”, it deserves more than a look—or, at least, to the sentiments expressed therein, I find myself no little bit sympathetic:

I have endeavoured to combine qualities which I consider essential to a good translation and which in many previous versions appear only partially or not at all.

First among these qualities I would reckon that of fidelity to the original. A brilliant paraphrase, however creditable to the translator, is fair neither to the author whose interpreter he professes to be nor to the public which expects—and rightly so—to be given a version approximating, as closely as the difference of idiom will allow, to the original work.

Oakley continues on to give the following explanation of the meter:

. . . the metre selected for the present translation is so elastic and accommodating that it has been found possible to reproduce the Latin with great exactness, so that only in one or two instances does the English differ from the Latin, and that mainly by the addition or suppression of an unimportant word.

Oh, I like that. (In fact, every new paragraph in this Note makes me think “nice! I ought to quote that!”—but I shall try to control myself.) Too, the following explication of one of the translation’s goals resonated with me more deeply than I would have expected:

The Aeneid is a long poem, consisting of many thousands of lines. It is also a story. These two facts seem to have been forgotten by several translators, who in their anxiety to give their work as ‘poetic’ a form as possible have, by rather tortuous inversions, unnecessary and wearisome archaisms and other devices, lost a great deal of the clarity and connection of the original. It is hoped that the straightforward order of words adopted in this new version will enable the reader (or better still, the listener) to follow the thread of the story without having to unpick any obstructive syntactical knots.

Emphasis added: this is a neat summary of an issue I’ve often felt, vaguely, when reading classics, but which I have not heretofore seen put into words. This is, I think, the primary reason that it is more difficult for me to enjoy some of ‘em as much as I do a modern novel: the need to pause and “unpick” the “syntactical knots”—and not (emphatically!) any deficiency in the narrative itself.

(Funnily enough, the translator of another of my favorite versions, J. W. D. Smith, takes exactly the opposite line… hm. Well, what’s that they say about consistency—something about “last refuges” & “the unimaginative”?—)

Oakley follows this with some raillery against translators who feel the need to “dress up the text in the outmoded finery of an older poetic convention”, assuring us that the humor & “homely” atmosphere Vergil occasionally offers up shall be present (he hopes) in the English too.

A final choice excerpt; here is also where I would normally say “the entire Note is worth reading”—except I will have now quoted about half of it already (it’s not very extensive, compared to e.g. Fagles’… just packed with bold & hearty flavor!™):

In English, a language where consonants abound, it is not possible to reproduce the musical effect of the Latin, with its many open vowels, but here at least an attempt has been made to do so. Tennyson, in an often-quoted line, hails [Virgil] as the ‘wielder of the stateliest measure [i.e. hexameter] ever moulded by the lips of man.’ Virgil married this Greek measure with the genius of the Latin tongue, giving it a perfection which, of its kind, has never been surpassed. To hear a Virgilian paragraph read is like sitting by the shore and hearing the waves come in, each the fellow of its resounding successors, yet each in some way subtly different, each with its own music. The wonderful variety which Virgil introduced into the hexameter, his inspired use of the pause, his felicitous alternation of spondaic gravity with dactylic lightness—these are qualities which the translator must essay to mirror in his own version if it is to have the same effect on his readers as the original has on him, which is surely what he most desires.

(An echo of Dryden, there, in the unfavorable comparison of English to Latin phonology. For myself, I rather prefer a good assortment of consonants; languages such as the Polynesian tongues, famously vowel-y, are often thought “beautiful” & “fluid”… but I’ve never liked that sort of sound nearly as much as—say—Slavic or Germanic diction.)

As mentioned above, re Ferry’s words, this sort of monstrously erudite linguistic analysis both gives me faith in the translator, and makes me eager to read whatever exemplifies the qualities mentioned therein. Anyway, enough puffery; let us examine the result of Oakley’s efforts:

▼ Frederick Ahl (2007) ▼

Notable Notes: Verse (dactylic hexameter)(!); 1:1 line count; very extensive effort to transpose all elements of Vergil’s Latin into English. Includes opening lines.

It has been a truism, in nearly all of these Introductions & Translator’s Notes & so forths, that an English dactylic hexameter simply isn’t possible. Our language simply doesn’t conform to the meter, say they; if you’ve managed such a couplet that scans, you’re already a wordsmith, and ought to quit while you’re ahead—no good can come of pushing it.12

And yet—here is Ahl: claiming to have done over 9000 lines of this Vergilist’s Grail. Naturally, I was a bit excited to crack this one open. (I mean, go back & re-read what Oakley says, and quotes Tennyson as saying, about dactylic hexameter!)

So: what does Ahl have to say about the work of translating Vergil? Quite a lot, as it turns out—and it’s all fascinating; once again, I have had to (heroically, in my view) resist the temptation to just copy-&-paste the entire dam’ thing.

To start us off, Ahl explains his choice of poetry over prose:

I don’t know how to refashion poetry into prose without losing the essence of what makes the original poetic. An epic poem must sing.

Fair enough; unlike J. W. D. Smith (below), Ahl attempts to make his Aeneid a “work of literature in its own right”, so that readers will “be able to sense through it that the original really is as good as its admirers claim”.

But like Smith—and unlike (e.g.) Ruden—Ahl has endeavored to render each particular Latin term with the same English word throughout; this fits neatly in with his desire to make the lines match—closely enough, as he says, for the “struggling Latin student” to use them as a “crib”.

(Wow: literal and literary! A monstrous chimera, then—or a true exemplar of the translator’s art?)

…But unlike Smith and like Ruden, he feels the idiom “has to be more or less contemporary, as direct and Anglo-Saxon as possible . . . unless special emphasis is required”—so that it will thus be both an easy read, and a faithful one. But!—do not think that this means we aren’t getting a nice heaping serving of technical poetics talk, too:

Athough my idiom is informal, often colloquial, I have used a version of Virgil’s ancient hexameter, a swift-moving line varying between twelve and seventeen syllables, divided among six feet, each of which carries its principal stress on the first syllable. . . . The first syllable of each line is always stressed. Here is an example of what I mean, with the stressed first syllables accented (3.583–7):

Hereupon, we get into some really interesting stuff. I am probably wrong to say that no other translator has yet mentioned the following, but I certainly do not remember reading of any efforts to transpose such elements into the English:—

The Aeneid, like much ancient (and some medieval) verse in European languages, uses not only regular metre but also carefully crafted resonances of sound. By this I do not mean rhyme (which Virgil hardly ever uses), but elaborate patterns of wordplay, including anagrams, which have not been a distinguishing feature of English poetry since Chaucer’s day. . . . Modern English translations of Chaucer, in fact, routinely suppress almost all his wordplay. I have followed the opposite course with Virgil. Wherever he uses two or more Latin words of similar sound or structure in close proximity, I have tried either to reproduce the effect in English or to express it in some other way.

Anagrams are more of a problem, since they usually cannot be ‘heard’ in English: ‘thread’ and ‘hatred’, for example, are anagrams only by conventions of spelling. In Latin, anagrams are audible. Latin letters have fairly predictable values regardless of placement within a word. [13] . . . To approximate the effect of Virgil’s anagrams I therefore had to depart at least a little from the ‘dictionary’ meaning of the text, and thereby invite accusations of mistranslation.

One does not have to understand Latin to see the problem. Here are the only two words in one of Virgil’s incomplete lines, Aeneid 7.702: pulsa palus. The poet is describing the ripples in the surface of a lake (palus) caused by the sound of the cries of swans striking (pulsa) its surface. The impact of the sound destabilizes and rearranges the elements of the word palus itself, not just of the lake the word indicates. The closest I could get was ‘pools’ and ‘loops’. Whenever syllables have to be inverted, I make their sound, not their spelling, the basis of my equivalent wordplays.

[ . . . ]

I have transposed Virgil’s puns, anagrams, and other figured usages into comparable but generally less intrusive figures in English without leaving the ‘dictionary’ sense too far behind. I rarely trespass farther than making nemus ‘a wooded area’ or ‘a (wooded) hollow’ rather than ‘a wood’. . . . This translation will, nonetheless, read quite differently, in several places, from many others since it retains elements that are usually jettisoned.

Puns? Anagrams? I was aware that there was “wordplay”, in Vergil’s Latin, but was neither aware of its extent nor of the exact forms that it took; and, had I been aware, I would not have thought it possible to really replicate. Ahl that’s some amazing stuff! (…heh heh—)

Just as reading that Ahl went for dactylic hexameter intrigued me, that final line intrigues me; a translation reading “quite differently” is indeed what one might expect, considering the elements retained by Ahl & “jettisoned” by his fellows. In light of this, the line takes on the cast of a friend promising that one has a gift in the mail.

There is (as ever, apparently) much more worth reading here, but I’ll close with a final two excerpts. First, a bit on Ahl’s “philosophy-of-translation”:

The Aeneid is often so translated as to accommodate either the widely accepted assumption that it is Virgil’s intent to glorify Rome and its emperor, or the increasingly popular counterassumption: that his intent is to mount a covert attack on Rome and the Caesars. The translator has no business imposing any such intentionalist framework. . . . English, with its vastly larger vocabulary than Latin in most areas, allows one to generate distinctions Roman writers had no means of expressing, and to justify changes in the original by using the dictionary shrewdly. Translators routinely render the adjective superbus differently, for example, depending on whether they (as translators) approve or disapprove of the person or place it is applied to, thereby conveying the false impression that this is what Virgil is doing. Although the ‘doorposts’ of a monster’s cave and of a god’s temple are described by the same adjective, superbus, those of the cave often appear in English as ‘arrogant’ or ‘haughty’, those of the temple as ‘proud’. I follow Virgil and use ‘proud’ in both cases, since pride can be virtue or vice in English.

[ . . . ]

Wherever I sensed the text leading me in different directions at the same time, I have left the reader the ambiguity or contradiction Virgil left me.

A nice instance of appreciation for English, there—unusual, in Latinists.

Finally, some praise for Vergil, and another exciting promise: although it is a running theme throughout all of these Notes and Introductions that the Aeneid is rather melancholy, F.A. finds much to chuckle over as well:—

I realized as I translated the catalogue of troops in Book 7 that Virgil had, throughout, leavened what I once thought flat and uninteresting lines with an often ebullient wit. We have no business making poetry dull because we disapprove of wordplay. To shear away Virgil’s luxuriance is not to separate the painting from a (superfluous) gilded frame, but to lacerate the canvas. Like Shakespeare and the Greek tragedians, Virgil grasped that humour and earnestness are not mutually exclusive in art, any more than they are in life. We should read the Aeneid, not in solemn homage, but for enjoyment.

[ . . . ]

However much Virgil conveys the impression that he is simply recounting the traditional “Tale of Aeneas’, there is reason to believe that he created most of the story and its extraordinarily vivid cast of mythic and fictional characters (almost all new to full epic characterization) all by himself out of scattered fragments.

There is really nothing to rival this achievement in Greek and Latin poetry.

▼ Len Krisak (2020) ▼

Notable Notes: Verse (rhyming iambic hexameter couplets)(!); 1:1 line count; extensive effort to create English poetry with all suitable elements of Vergil’s Latin.

This is another interesting & fairly unique effort. We’ve seen prose; we’ve seen iambic pentameter; we’ve seen rhyming couplets (Dryden); we’ve seen iambic hexameter (Bartsch); and we’ve even seen dactylic hexameter (Ahl)—but we’ve not yet seen rhyming couplets in iambic hexameter.

That alone makes this intriguing (as does the 1:1 line count, which I always like to see). Krisak makes the argument that un-rhymed verse—however faithful to the Latin—simply doesn’t produce the same effect in our modern ears as it might have for a Roman audience; doesn’t sound like poetry.

And—I have to admit: though I have obtained an appreciation for “metric verse” after long exposure, I’m not sure I will ever feel it quite as deeply as I do rhyme. (It was interesting, to my mind, to learn how late rhymed verse was refined, in our poetic history—at least, over here in the West; I don’t know much about the rest14 —and it never quite made sense to me: how, I ask, could not the ancients see how so much better that rhymed verse be?)

Now that I’ve destroyed your image of me as a classicist of godlike taste & erudition, let us hear directly from K-Sak:

. . . Because classical meter is based on the value of quantity—length of syllables, whether by position or by the inherent nature of the vowel of that syllable—and not, as in traditional English prosody, by the stress or accent on syllables, translators through the centuries have tended to substitute equivalent feet in English for Latin feet. In practice, this means that where a Latin poet would treat a dactylic foot of three syllables as long-short-short, the English-language poet would create dactyls out of a stress-unstressed-unstressed triad.

[ . . . ]

But there is a further problem in carrying over Latin feet into English equivalents: How does the modern poet sustain almost nine thousand lines of dactyls created by stress or accent? Tennyson famously experimented with possible solutions to this problem and wryly concluded it was next to impossible. And here are the first four lines of Byron’s “Bride of Abydos”:

Know ye the land where the cypress and myrtle Are emblems of deeds that are done in their clime? Where the rage of the vulture, the love of the turtle, Now melt into sorrow, now madden to crime?Immediately apparent is the considerable degree of metrical finagling needed to keep these lines dactylic.

For these reasons, I have rendered Virgil’s dactyls as iambs—that ancient standby metrical foot of the great preponderance of English poetry. Hence, iambic hexameters—six-foot-long lines in the pattern most readers of English verse will recognize immediately. [ . . . ]

This brings us to a last—and most important—decision: to rhyme my hexameters in couplets. I fully realize that there is almost no rhyme in Latin verse, and that true scholars may well be appalled to see Virgil dressed in the robes of Yeats and Frost and Wilbur, but I also feel strongly that the Aeneid is a poem, and I wanted to find some way to make the readers of this work feel that they were in fact reading a true poem in English. Virgil’s verse is musical and supple, with principles of sound and rhetorical figures in full play, from alliteration and consonance and assonance to chiasmus and adynaton and beyond. That I am no Dryden or Pope is too obvious even to mention, but I did want to stake a modest claim on the attention of my contemporaries, who will, as always with any poet, be my final judges.

Adynaton? Christ, you literary types—I’ve not learned so many news words in a single day since first reading LotR back in third grade! (N.B.: Carrying around a thick fantasy novel at school is a great way to make friends & be seen as a real cool cat—little tip for you younger readers, there.)

I’m not sure I do see the “finagling”, in those lines of Byron’s—unless “the love of the turtle” wasn’t a detail Lord B. had initially planned to include—but I’m nevertheless prepared to accept Krisak’s contention that it is very difficult to continue on like that. (I find that scansion in general doesn’t come too naturally in my own poetic efforts, either.)15

The results, then:

▼ Joshua W. D. Smith (2017) ▼

Notable Notes: Line-by-line translation (“half verse”?); 1:1 line count; parallel Latin text; extensive effort to obtain complete semantic fidelity to the Latin.

Smith writes that this is first & foremost an attempt to create an extremely faithful translation, and not a “literary” effort—“mine is a teacher’s translation, not a poet’s”, he writes. If it ends up “poetic and colorful” in English anyway, then so much the better—but the main emphasis is on items such as:

“consistency in word choice” (using the same single English term for each Latin word throughout, or as close to this ideal as possible, on both scene & entire-work levels)

“English line matches Latin line” (minimal rearrangement: if a word appears in an English line, its Latin counterpart was likely in that same line)

“English line matches Latin line, redux” (minimal rearrangement of word placement within a line)

“English word matches Latin word” (trying to use Latinate derivatives whenever possible)

“grammatical structures remain consistent” (active forms in the Latin are still active in the English, infinitives stay infinitives, etc.)

Pietas and its counterpart, furor, are left untranslated: Smith could not find a single English word that would fit all the senses of the former (something that has been noted in many of these introductions); and if pietas was going to be retained, he felt its opposite should be too, as a sort of mirror image.

I like all of this. My desire, in reading translations, is always firmly toward the “literal” side of the spectrum—I’m most interested in what was actually written in the original, and by-and-large I don’t trust a translator to be able to truly recreate the “feel” & beauty of the original (else, for one, they’d surely be known for creating a similar work in their own native language, right?).16

But, of course, few will look at a textbook and say “my God! it’s magical!”—so I have seen it mooted that yes, this is a great version to read… after you’ve already read & fallen in love with a more literary effort. I can see an argument for that; I’m making my way through this particular version now, though, and will update if I find that “hmm, would’ve been good to start off with this, actually.”

▼ W. F. Jackson Knight (1956) ▼

Notable Notes: Prose; ghostwritten by Vergil himself(!). Includes opening lines.*

Updating this page for other reasons, I thought to myself: “You know, I’ve been hearing many people recommend Knight—I ought to add ‘im, while I’m at it!”…

…but, though I thought I had saved near every academic article or XYZ Classical ReviewStudies essay on Aeneid translations, I cannot actually find the instances I seem to remember (bar one: in a 1978 piece for journal Greece & Rome, one D. E. Hill mentions that Dr. Brinley Rees, a Welsh classicist, thought Knight’s was the finest translation then extant—although Hill himself is, at best, ambivalent).

Nevertheless, Knight’s not unknown, and he has recorded a few relevant thoughts in his Introduction. This last opens with a (rather lovely) paean to Vergil’s poetic brilliance, then goes on to ask & answer: why—considering all the rhapsodies about Vergil-as-a-poet—a prose translation?

All this [virtuoso Vergilian versification] must be lost in a prose translation, but a great deal, far more in fact, ought not to be lost; for what counts most of all is the story, the drama, and the meanings which the story and the drama reveal. . . . But, so subtle and elaborate is Virgil’s art . . . that it is hard to be sure that any omission or any expansion will be harmless [and yet] his power to say much in little is so striking, that at least some expansion is necessary, and indeed much more than is normally inevitable when poetry, the medium of suggestion, is to be translated into prose, the medium of statement.

In language, Virgil was a master of eloquence in every style. “Apocalyptic majesty”, as it has been well called, and the softest pathos in a still, small voice, are equally characteristic of his Latin. He normally wrote with dignity and a certain formality. But . . . occasionally there is an effective colloquialism and even here and there something like slang. [ . . . ]Obviously it must be contemporary [yet timeless] English, reasonably smooth and free from any serious jolts. To make the story of the Aeneid dull, slow-moving, hard to read, or obscure, would probably be the unfairest thing of all both to the reader and to Virgil himself.

. . . Clearly, the plan must be to let Virgil himself pass on what he has to say with as little impediment as possible. Perhaps, if there is a sincere attempt not to interfere with him, some at least of his supreme eloquence may come through.

Knight also mentions “playing it safe”, and striving for fidelity over artistry, then goes on to give a nice little overview of the Aeneid’s importance to Western literature.

I do like these sentiments—though he comes off as much more uncertain about his own ability (as a translator) than, say, Bartsch seems to be; whether this is to be taken as a good or a bad sign, I’m not sure—but the most interesting thing about this translation is: Vergil himself helped with it!

…or, at least, this recorded in his (Knight’s, not Vergil’s—) biography (apparently, by his brother, G. Wilson Knight); from a review of the same:17

When [Knight] began his Penguin Aeneid translation, T. J. Haarhoff, “who had for years claimed spirit-contacts with Vergil himself... now put his powers at Jack's service” (p. 382). Vergil visited Haarhoff “every Tuesday evening” and wrote out answers to questions raised by Knight, whom Vergil regularly called “Agrippa.” Knight told Haarhoff that “on comparing V.'s interpretation with that of the scholars, he generally found it the simplest and the best.” . . . Vergil then began to contact Knight “directly at Exeter” (p. 383) warning him “to go slow and be extra careful about the 'second half.'”

Well, there you have it: this is the authoritative translation.

…or, uh, maybe not—but it is not to be despised, perhaps, as much as that sort of nonsense would normally warrant; from the April 1992 BMCR review (by “Dan Harmon”) of the book Talking to Virgil:18

Curiously, Knight, while a genuine believer, also maintained a degree of independence and did not adopt all the responses which Haarhoff attributed to Vergil.

And, in another review19 of the same:

. . . clearly Haarhoff, or Haarhoff’s Virgil, influenced Jackson Knight's translation, but equally clearly Jackson Knight kept his critical faculties alert and did not blindly accept everything Haarhoff reported Virgil to have said.

Well… so one would hope! Let us behold, then, the only Authorized Edition™:

*(by Vergil’s request)

III. Conclusion?

There you have it: every translation & consideration worth thinking about. Cheers!

…okay, perhaps not. I know I’ve missed at least a few that ought to be here; and I’ve neglected to consider “extent of supplementary material”, too.

Still, supplementary material can always be found elsewhere, and so is of secondary importance. But—enough of this nonsense. Which one is best?

(It’s common practice, when asked about a “best” translation, to snivel about how there is “no such thing” & “it depends” on this ‘n’ that. Well, that’s not wrong—it is helpful to know if the requestor most values semantic fidelity, ease-of-perusal, artistic quality, or what-else-have-you…

…but even so: much like men, all translations are not made equal. This is a case of Pareto optimality: there is surely a point wherein fidelity must be compromised for art, or art for fidelity—but some versions are on that frontier, and some… aren’t!)

Of course, my analysis will inevitably be tainted (or, some would say, elevated, in my case—) by my opinion. Briefly (for once), then, here’s what I look for:

Fidelity, both semantic & metrical. As mentioned above, if there’s a spectrum between valuing “literal correspondence with original” and valuing “ease & familiarity for the contemporary reader”, I’m pretty far to the former side.

Verse. I can see the argument for prose, and am sympathetic to it, but it’s just too big a departure from The-Aeneid-as-anterity-knew-it.

1:1 correspondence with the lines of Vergil’s Latin. I could be argued out of this one, but I think it sort of forces some of the fidelity I desire into the outcome.

Shortlist:

Honorable mentions in (very) rough order:

Oakley

West

Mandelbaum

Fitzgerald

Lombardo

Kline

Top four side-by-side:

Krisak gave me my love for the Aeneid, and the impetus to study Latin; so it pains me to say this, but—I think like Ahl & Ruden most of all.

Ahl: More than anyone else, Ahl seems to have striven to capture every possible facet of the original: the meter, the wordplay, the assonance & alliteration, the meaning… it’s all there. Most must choose between “accurate, but not an object of literary value per se” vs. “poetic & artful, but not very true to the source”; for my money, Ahl has—somehow—managed to have his libum (archive), and eat it too.

Ruden: Sure, sure, it is not the Sacred Hexameter… but it is an extremely faithful rendering—more-so than most—and she still manages word choice finer than Bartsch’s & phrasing more natural than Krisak’s, to my mind’s… ear(?); and, not infrequently, her brevity makes it a smoother & easier read compared to Ahl’s (relative) prolixity.

(Also, in the introduction to her likewise-excellent translation of Apuleius’ Golden Ass, she mentioned that she likes Flashman; towering intellect & impeccable taste = confirmed.)

But truly, you cannot go wrong here: I flip-flop regularly between these four. I’m also very interested to hear what you, the good-looking & intelligent reader(s), have to say—perhaps I’ve missed something important? Donate Comment below!

(…he said, to the empty room. hint, hint—)

Fin.IV. Appendix 1

A few more comparisons.

“Big Four”:

(to-do: add Ruden/Fitzgerald/West/Smith comp, for overall/literary/prose/literal side-by-side)

Links:

V. Footnotes

Not to denigrate the Bible, I mean; it’s merely too familiar—the would-be bibliomancer wants to hear about obscure texts full of fell spells!

For the non-Latin-reading churl, anyway.

I’m trying my hand at coining some words. Another one I’m trying to make a thing is “whince”*, if the reader would care to join me in this important project.

*(from which, see?—)

Fitzgerald, Robert. “Dryden’s ‘Aeneid.’” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 2, no. 3 (1963): 17–31.

Okay, not really. I had written that before reading down to those illumining passages which I’ve ended up quoting… but I liked it too much to cut it—much, perhaps, like Dryden himself: quoting Fitzgerald quoting Johnson: “He was no lover of labor . . . [w]hat he thought sufficient, he did not stop to make better; and allowed himself to leave many parts unfinished, in confidence that the good lines would overbalance the bad.”

Emphasis added.

Unsure whether this is to be interpreted in the sense of “lacking”, or in the sense of “desiring”; both seem equally plausible, in context. Help.

I haven’t yet found any explication of the differences between the Latin text Dryden would have had available vs. that we have now. My impression is that, after the work of Philip Wagner (mid-19th cent.), revisions (archive) have been fairly minor (archive)—but this is still after Dryden, and I’m no expert. If & when I’m able to say something substantive, I’ll add an appendix about this.

“Big Four:” as a function of “popularity” weighted in some manner by “time since publication”—I figure that if a work published in 1900 is talked about roughly as much as a work published in 2020, the older one probably deserves to sit a bit higher. (⮬ back to Dryden section?)

Not really, but you’ve got to admit: the more obscure & confusing a concept is, the more the literati love it.

Smith, for example, writes that he purposefully tried to pick Latinate words.

I say “pseudo-verse” because it sure looks like poetry of some kind, and sort of reads like it too; and it is often listed as a verse translation; but there isn’t a consistent meter—as in Lewis’, above—and: Kline himself calls it a “prose translation”, so… hm.

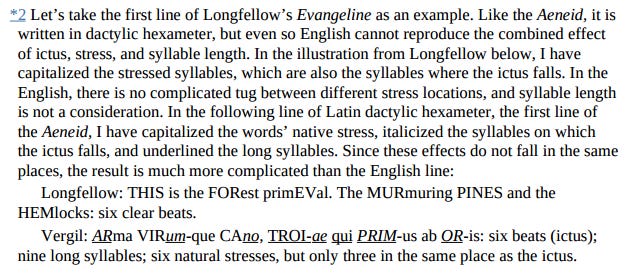

To be fair to the other translators, it appears that Latin (quantitative) dactylic hexameter produces effects that really can’t be found in English. Here’s Bartsch explaining it:

Here, Ahl adds the following, which I had never heard before & found fascinating: “Young Romans were trained to recite their letters (and syllables) as we recite numbers: backwards as well as forwards, and in various other groupings.”

Belay that—I do know that rhyme was used in Arabic poetry from way, way back. But this is not quite the same as it is in English; you can rhyme ten thousand lines with the same assonance—which somewhat cheapens the effect, to my ear.

Although… more naturally than to most, evidently: I am perennially surprised to find that (very) many would-be poets are able to jot down verses reminiscent of the old limerick:—

There was a young man of Japan

Whose poetry just wouldn't scan;

He said, with a sigh,

"I think I know why:

"I just always try to cram in as much on the last line as I possibly can." —without, apparently, noticing anything wrong with them.

Well, perhaps not. Some people—i.e., me—do find the best expression of their talent in linguistic “detail work”: collating, editing, refining, researching… it’s more satisfying, for me, to produce a “critical edition” than it is to produce something ex nihilo.† (Paradoxically, though, I’m more of an “idea[s] guy”, & despise detail work, in other areas. I felt it was important that you know this.)

†This is very often an issue when I am trying to author an original work; I find myself writing a single chapter… and then happily editing & refining for hours on end. No! Dammit, Kvel! You’ve got to actually get it all down first!—

Classical Association of the Atlantic States; JSTOR; Project MUSE; Johns Hopkins University Press (ISSN 1558-9234), 70, 1977. Review by: William M. Calder III

T. P. Wiseman; ISBN 0-85989-375-8. A volume that—treacherously, considering the title—is not actually about Knight, overall; also, this review is cited incorrectly all over (wrong BMCR date, wrong link, wrong archive link, different wrong BMCR date…) & it took me some effort to track down. But I did it, for you.

SCHOLIA, Natal Studies (ISSN 1018-9017); vol. 2, 1993; pp. 121-124. Review by: Anne Gosling

This was magnificent! I just finished reading The Aeneid for the first time (Ruden) and I am now in the deliriously glorious rabbit hole of exploring/ comparing other translations. This read was thoroughly enjoyable (and humorous!) and I learned a lot. Thanks!

Interesting post! After reading it I feel like I really know the first page of the Aeneid.

From this comparison, I feel most drawn to the Mandelbaum version. That's ignoring considerations of faithfulness, and just choosing the one that sounds the best to me. I like the rhyme and alliteration.